Blog posts

Chapter 74: The Mystery of Mysteries

Previous Chapter Next ChapterMysteries. Everybody thinks they know what they are. No one does.

Scholastic’s genre chart says:

Purpose: To engage in and enjoy solving a puzzle. Explore moral satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) at resolution. Consider human condition and how to solve or avoid human problems.

study.com says:

The purpose of a mystery novel is to solve a puzzle and to create a feeling of resolution with the audience.

education.com says:

The plot usually begins with action, intrigue, or suspense to hook the reader. Then, through a series of clues, the protagonist eventually solves the mystery, sometimes placing himself or herself in jeopardy by facing real or perceived danger. All information in the plot (clues) could be important in solving the case, yet in some cases, the author presents misleading information (a red herring) to challenge the reader and the detective. With foreshadowing often used to heighten the suspense, there usually will be several motives for the crime, lots of plot twists, and plenty of alibis that must be investigated. The solution to the crime must come from known information, not a surprise villain introduced in the last chapter of the book; however, the clues must be cleverly planted so that the mystery is not solved too easily or too soon

PBS says:

The formula Conan Doyle helped establish for the classic English mystery usually involves several predictable elements: a "closed setting" such as an isolated house or a train; a corpse; a small circle of people who are all suspects; and an investigating detective with extraordinary reasoning powers. As each character in the setting begins to suspect the others and the suspense mounts, it comes to light that nearly all had the means, motive, and opportunity to commit the crime. Clues accumulate, and are often revealed to the reader through a narrator like Watson, who is a loyal companion to the brilliant detective. The detective grasps the solution to the crime long before anyone else, and explains it all to the "Watson" at the end.

Wrong. All wrong![page_break]

Sherlock Holmes Stories are About Sherlock Holmes

I started thinking about this because I’ve been reading a lot of books on writing, and I keep seeing Sherlock Holmes used as an example of a shallow character. I think the people who do this must not have read many Sherlock Holmes stories. Their reasoning appears to be thus:

Genre fiction does not have interesting characters.

Mystery is the simplest genre, and so should require the simplest characters.

Sherlock Holmes is the best-known fictional detective.

Therefore, Sherlock Holmes is the simplest of characters.

Sherlock would not approve.

Sherlock Holmes is the original source of fan-fiction. People are still obsessed with Sherlock Holmes. And it takes only a passing familiarity with either the original stories, or with the fan-fiction, to see that what fascinates people with Sherlock Holmes stories is Sherlock Holmes.

Because I seldom read mysteries other than Sherlock Holmes (since, as we all know, they have very simple characters), I thought for a long time that this accusation of simplicity was uniquely unjust to Sherlock Holmes. Then I remembered Monk, television’s obsessive-compulsive detective. He was another exception. And Father Brown, G. K. Chesterton’s soft-spoken detective. And Sam Spade. And Rick Blaine from Casablanca. Even The Pink Panther’s Jacques Clouseau. Almost every detective I knew was an exception—and all in similar ways!

What are Genres?

Let’s back up for a moment. What are genres? Why is there a genre called Western in the bookstore, when the world’s output of Westerns today is smaller than fimfiction’s output of ponyfic?

I think that every genre originates around a central narrative about a way of looking at the world. If I use that as a definition of genre, a lot of things become genres that we currently think of as styles, like Medieval painting, romantic poetry, and Nazi propaganda posters.

Once a genre is established, it mutates and splinters into sub-genres. It gets subverted, meaning its message is reversed. It gets parasitized, its subjects and tropes used as a host to camouflage content from other narratives. (For example, John Keats wrote neo-classical poems in the surface style of romantic poems, and Star Wars is a fantasy masquerading as science fiction.) And it gets hollowed out, retold by hack writers who copy all the trappings of a genre, but never notice that a story is more than a plot.

I see these as the core narratives of some existing genres:

Fantasy: The world is fundamentally just. Virtue will be rewarded in the end, even when it defies logic. See my post "Fantasy as deontology”.

Subversion (Black Company, Game of Thrones): The world is fundamentally unjust, and the virtuous will suffer.

Horror: Evil in the world comes from bad people who’ve been corrupted, and the way to fight evil is to identify those who are impure or corrupted (e.g., vampires, zombies), and kill them.

Subversion (Heart of Darkness, Fallout: Equestria): Evil comes from good people.

Romance: A good man is a bad man who loves a good woman.

Science fiction: The world fundamentally makes sense. Everything can always be understood. Problems are caused by misunderstandings and inadequate information.

Subversion (“Frankenstein” (the book, not the movie), Michael Crichton): Science is spiritually arrogant and inherently dangerous.

Science fiction is an oddball genre, because its original form (ignoring “Frankenstein”), hard science fiction, is uniquely non-character-oriented.

Western: The world is a violent place that cannot be ruled by law, society, or authority. Government is inherently corrupt. Only lone virtuous violent heroes, unconstrained and uncorrupted by social structures, can cleanse society of its parasites.

Subversion (High Noon): Society doesn’t deserve to be saved.

Subversion (The Searchers, Unforgiven): Good guys are just bad guys with good luck and good press.

Mysteries and westerns seem similar. Both conventionally star a lone, eccentric hero who solves problems no one else can, through violence in westerns and logic in mysteries. But the attitudes feel different to me; westerns are drenched in testosterone and self-righteousness in a way that mysteries aren’t. Also, 64% of western readers are men, while 70% of U.S. mystery readers are women. So I won’t assume mysteries are just westerns for nerds.

(Notice that the core narrative of every genre is a dysfunctional, sometimes psychotic ideology. I wonder why that is? Are genres a type of cult?)

So what’s the core narrative for mysteries? Let’s start by looking at famous mysteries.

Famous Fictional Mysteries

The earliest mysteries are Edgar Allen Poe’s stories starring his detective Auguste Dupin: “Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), “The Mystery of Marie Roget” (1842), and “The Purloined Letter” (1844). (Although the word “detective” didn’t yet exist.) Dupin has super-human powers of observation, concentration, and analysis, but explains his deductions as being simple and obvious. He has an odd detachment from humanity which manifests in his voluntary seclusion, his preference for leaving his home only at night, his lack of interest in being recognized for his accomplishments, and his boasting that “most men, in respect to himself, wore windows in their bosoms.” He disquiets his unnamed Watson by responding to the gruesome murder of a mother and daughter by saying, “An inquiry will afford us amusement.” He is active, bold, and delights in laughing at the police and in concealing how far he has gotten in order to make a sudden dramatic revelation. In short, he is the model for Sherlock Holmes. Jean-Claude Milner claimed that Dupin is the brother of the genius villain D___ in “The Purloined Letter”.

Sherlock Holmes appeared in stories written from 1887-1927, and is based on Dupin, as evidenced by many similarities between them, by Conan Doyle's citing Poe's stories as a model, and by Holmes resenting being compared to Dupin in the first Holmes story and immediately claiming differences between them which do not, in fact, exist. Holmes is superhumanly observant and intelligent, arrogant, detached from humanity, never visibly emotional, and seemingly unwilling or unable to fall in love. He had no respect for conventional thought or morals, and sometimes let criminals escape when he judged their crimes justifiable. Between cases he often descends into depression and drug abuse. His lifetime adversary, Professor Moriarty, is a sort of evil Holmes.

G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown (1910-1936) is a humble, unimpressive priest who solves mysteries. In many stories, some other characters laughs at the little priest’s plain appearance, jokes about the priest’s presumed simplicity and superstition, concludes the mystery has a supernatural explanation, and is then humiliated when the priest reveals a natural explanation. Unlike Holmes, who uses reason guided solely by empirical observation, Father Brown uses reason guided by observation but also by intuition, a reflection of medieval scholasticism.

Agatha Christie’s Hercules Poirot (1920-1975) is a physically unimpressive old Belgian exile in England, introduced as “a small man muffled up to the ears of whom nothing was visible but a pink-tipped nose and the two points of an upward-curled moustache.” He speaks apologetically yet impudently, is neurotically fastidious about his appearance and the shine on his shoes, and tries to always keep a bank balance of 444 pounds, 4 shillings, and 4 pence. One of his techniques is to make people dislike and underestimate him:

It is true that I can speak the exact, the idiomatic English. But, my friend, to speak the broken English is an enormous asset. It leads people to despise you. They say – a foreigner – he can't even speak English properly.... Also I boast! An Englishman he says often, "A fellow who thinks as much of himself as that cannot be worth much." … And so, you see, I put people off their guard.

He sometimes lets criminals escape, or to be punished extra-judicially. In 1960, Christie, probably a little tired of him, called him a "detestable, bombastic, tiresome, ego-centric little creep". I haven’t read these stories.

Sam Spade, the semi-hero of The Maltese Falcon (1929 novel, 1941 film), was the original hard-boiled noir detective. I think this story is especially illuminating. It is to the usual detective story as a story in which the hero fails to change is to stories in which the hero changes. This is symbolized by the fact that, though Spade unravels the murders that happen, he never solves the original mystery--he never finds the falcon.

Wikipedia says, “Sam Spade combined several features of previous detectives, most notably his cold detachment, keen eye for detail, and unflinching determination to achieve his own justice.” Sam gives his view of the world towards the end of the novel:

“Now on the other side we've got what? All we've got is the fact that maybe you love me and maybe I love you."

"You know," she whispered, "whether you do or not."

"I don't. It's easy enough to be nuts about you." He looked hungrily from her hair to her feet and up to her eyes again. "But I don't know what that amounts to. Does anybody ever? But suppose I do? What of it? Maybe next month I won't. I've been through it before--when it lasted that long. Then what? Then I'll think I played the sap. And if I did it and got sent over then I'd be sure I was the sap. Well, if I send you over I'll be sorry as hell--I'll have some rotten nights--but that'll pass."

Sam does not love her, and she doesn’t love him, not in any sense that wouldn’t degrade the word. She’s an evil bitch and he sends her to prison. But his debate with himself shows that he thinks maybe he does love her, because what he feels for her is the closest he can think of as to what “love” might mean.

The novel ends on a note of psychological horror: Sam tries to flirt with his secretary Effie, teasing her a little cruelly for her innocence, but she shrinks from him in revulsion at—what? What he did? What he is? Or that he can do such things and not be broken by them? Sam turns pale on seeing the distance between them, and turns instead to his dead partner’s wife, whom he doesn’t like very much but had been banging—which is, I think he realizes at that moment, all he’ll ever know of love.

The girl's brown eyes were peculiarly enlarged and there was a queer twist to her mouth. She stood beside him, staring down at him.

He raised his head, grinned, and said mockingly: "So much for your woman's intuition."

Her voice was queer as the expression on her face. "You did that, Sam, to her?"

He nodded. "Your Sam's a detective." He looked sharply at her. He put his arm around her waist, his hand on her hip. "She did kill Miles, angel," he said gently, "offhand, like that." He snapped the fingers of his other hand.

She escaped from his arm as if it had hurt her. "Don't, please, don't touch me," she said brokenly. "I know--I know you're right. You're right. But don't touch me now--not now."

Spade's face became pale as his collar.

The corridor-door's knob rattled. Effie Perine turned quickly and went into the outer office, shutting time door behind her. When she came in again she shut it behind her.

She said in a small flat voice: "Iva is here."

Spade, looking down at his desk, nodded almost imperceptibly. "Yes," he said, and shivered. "Well, send her in."

Isaac Asimov wrote a series of detective stories and novels (1953-1986) starring Elijah Bayley, a human, and R. Daneel Olivaw, a robot, in a world in which robots have no freedom or rights. The robopsychologist Susan Calvin, a human who identifies with robots, also appears in some stories. The plots usually turn on questions of how to interpret Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, while their themes often deal with human prejudice against robots, and the philosophy of good and evil.

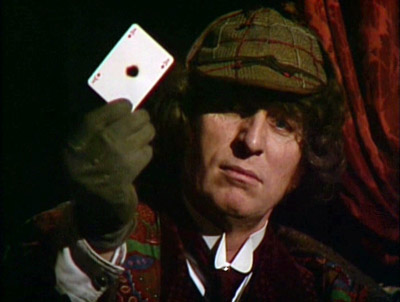

Dr. Who (1963-today) is called science fiction, but the plot is often a mystery: The Doctor appears someplace and sometime where things are not as they at first appear, and he must puzzle out what is happening, and prevent some bad thing from happening. The Doctor’s character is a warmer, fuzzier Sherlock Holmes, who travels with one or more semi-disposable Watsons and finds humans silly but endearing rather than tiresome. (That photo is of Tom Baker playing Dr. Who playing Sherlock Holmes.)

The Pink Panther’s Jacques Clouseau (1964-2009) is a bumbling idiot who solves cases mostly by accident. Yet he’s also dedicated, energetic, and creative (witness his elaborate training methods). Much of the humor comes from Clouseau misunderstanding everything that he sees and, far from being a detached observer, managing to remain all the time in his own fantasy world.

Including The Pink Panther here is like including Spaceballs in an analysis of high fantasy. I don't expect it to match thematically, since it's a parody, but it will share some attributes.

The Great Brain (1967-1976) is a series of children’s detectivish novels whose child protagonist, Tom Fitzgerald, alternates between solving crimes and committing them. He cheats his neighbors so often that the other kids eventually kidnap him and put him on trial in The Great Brain Reforms. His younger brother J.D. is his Watson. The stories often contrast Tom’s intelligence but lack of empathy with J.D.’s lesser intelligence but greater humanity, and show Tom mastering the world intellectually, but not really understanding how to relate to it.

Tony Hillerman’s Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee (1970-2006) solve crimes on a Navajo reservation. I haven’t read any of them, but I’ve been aware of them for a long time. I’ve read that they’re usually about conflicts between Indian and white culture, religion and materialism, and rich and poor.

Mma Precious Ramotswe is the detective in Alexander McCall Smith’s The No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency (1998-2015). She’s a woman who was educated in Mochudi, the 10th largest city in Botswana, then moved to a very small village, where she decided to set up a detective agency. She believes she values Botswana’s traditional ways more than the modern white ways, yet her independence, modern upbringing, and dislike of marriage bring her repeatedly into conflict with the village’s strongly patriarchal and family-oriented attitudes. [If you’re gonna read just one detective novel, I’d suggest one of these.]

Adrian Monk is the consulting detective in the TV series Monk (2002-2009), whose obsessive-compulsive behavior causes him to be unable to hold down a job or function in society, but also makes him aware of tiny details that help him solve cases. Much of the humor of the series is that crimes that are impossible for most people to solve are easy for Monk, yet everyday tasks that most people consider trivial are impossible for Monk.

House, a TV series from 2004 to 2012, stars Dr. House as a sociopathic but brilliant surgeon who is basically a less-fuzzy Sherlock Holmes.

Dexter is the forensic expert / detective / serial killer star of a novel (2004) and a TV series (2006-2013). His father taught him to use his uncontrollable homicidal urges for good, by killing very bad people.

A Mystery is About the Detective

Why do mysteries always have just one or two detectives? Why don’t we see great mysteries in which a team or a town cooperates to solve a mystery, like on CSI, or Scooby Doo?

If mysteries are simple whodunits, why are the detectives in great mysteries always so eccentric and so finely-detailed?

Because the central narrative of the mystery isn’t about the mystery. It’s about the detective.

What can we say about the detectives in great mysteries?

1. The most-important trait of a detective in a mystery is not intelligence. It’s that the detective is a misfit.

The detective is a stranger in a strange land who sees its inhabitants more clearly and objectively than they see themselves. Yet, despite this--or because of it--he can’t establish normal emotional connections with them.

Detectives are Misfits

Auguste Dupin: Exiled from the aristocracy, lives in seclusion, only comes out at night, sees humans as a source of amusement. Single.

Sherlock Holmes: Prefers anonymity, scorns emotions, emotionally crippled, dangerously depressed and bored with humanity. Single.

Father Brown: A deliberate misfit, he dismisses the world’s values and represents Catholic values in contrast to it. Single and celibate.

Hercules Poirot: An oddball foreigner who does not care whether people like him. Single.

Sam Spade: An almost nihilistic mercenary whose crucial strength turns out to be his cold, unemotional self-interest. Single.

R. Daneel Olivaw: Literally inhuman. Single.

Dr. Who: Literally an alien. Single, except for whatever he’s got going with River. I haven’t kept up.

Jacques Clouseau: Lives in his own fantasy world. Single.

The Great Brain: Verges on sociopathic; unable to make friends.

Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee: Living between and mediating between the Indian and the American, the religious and the secular, the rich and the poor. Joe: Married for one book, widowed for eleven. Jim: Single and dating for 11 books, married for one.

Mma Precious Ramotswe: A fiercely independent woman trying to do a “man’s job” and refusing (for several novels) marriage offers; a city person in a small African village; a traditionalist who isn’t traditional. Single; later marries.

Adrian Monk: Freakishly weird; unable to cope with even simple social interactions. Widowed.

Dr. House: A sociopath with a live-in prostitute.

Dexter: A homicidal psychopath. Single; dates. Should be faking his feelings, but the show never had the nerve to portray psychopathology honestly.

2. The detective stands outside or above the law and conventional morality.

He may consider his own justice (Sherlock Holmes, Hercules Poirot, Dr. Who), or his tradition of justice (Father Brown), superior to conventional morality or the law. He may solve crimes for entertainment or revenge that other people would solve out of moral outrage or patriotism (Dupin). He may be a part-time criminal or con-man himself (Sam Spade, The Great Brain, House, Dexter). He may not be recognized as a person under the law (Daneel Olivaw). If there is a criminal mastermind, the detective will have more in common with that mastermind than with other people (Sherlock & Moriarty, Auguste Dupin & D___, Dr. Who and his two great enemies, The Master and Dr. Who).

Notice that the two examples that fit both #1 and #2 least well are the two cross-cultural detective series, by Tony Hillerman and Alexander McCall Smith. I predict these are going to represent some variation on the pattern. In the standard detective novel, we have two worldviews: the conventional worldview, and the world of the detective. I expect that in the cultural mystery, the two worldviews are those of the two cultures coming into conflict, and the detective is someone with one foot in each. The detective then does not need to be especially odd, nor to stand outside both cultures.

So, the purpose of a mystery is to contrast two worldviews. Can I be more specific? Well, usually either the detective laughs at or scorns the follies of the world (Dupin, Holmes, Spade, The Great Brain, Dr. Who, House),or the world laughs at the detective (Father Brown, Poirot, Clouseau, Ramotswe, Monk). The detective considers himself or is presented as superior to his clients (Holmes, Father Brown, Great Brain, Dr. Who, House) and/or the clients consider themselves superior to the detective (Holmes, Father Brown, Poirot, Clouseau?, Monk, Ramotswe). Yet the detective often feels his isolation from society painful, and the reader is asked whether the detective’s talent is a blessing or a curse (Holmes, Poirot?, Spade, Daneel Olivaw, Dr. Who, The Great Brain, Monk, House). That last one covers all of them except Dupin, Father Brown, Clouseau, and the cultural detectives, so I think that’s the key.

Here’s one possible point 3 to conclude from all this:

3a. The social function of a mystery is not to show that humans are foolish and that a detective with a little logic is superior to them, but quite the contrary—to reassure us, by showing the detective’s incomplete and solitary life, that our foolishness is wisdom, and careful analysis or greater intelligence would only make us unhappy.

Alternately, the function may be 3b. To argue that neither worldview is complete, and that no worldview can be complete—to gain empirical understanding, you must give up something else. This would make detective novels fundamentally modernist, and very similar thematically to the second book of Don Quixote, and to Henry James novels!

Neither conclusion maps back well onto all of my dataset. Not onto Clouseau, but I didn't expect it to. Not onto Father Brown or the cross-cultural mysteries. Let's handle them separately:

4. The social function of a cross-cultural mystery is usually to contrast an older culture with a newer culture that now dominates it, and heighten respect for the older culture.

Hillerman and Smith’s mysteries are noted for the respect they show for Navajo and traditional Botswanan (sp?) culture, not for the respect they show for Western culture. The Father Brown stories, by this understanding, are also cross-cultural mysteries; they’re meant to heighten respect for Catholicism [1]. This still leaves us with Dupin, Daneel Olivaw, and Dr. Who unaccounted for.

[1] Father Brown is also an exception because the stories are from an entirely different artistic tradition—the tradition that I call propagandist, which includes nearly all medieval fiction, in which art is used not to ask questions, but to claim that the authorities already have all of the answers. That's why it doesn’t present its two worldviews (Catholic and secular) even-handedly; the Catholic always comes out on top.

The anti-intellectualism of 3a may account for Dr. Who's strong anti-intellectualism, which is most peculiar in a show that calls itself science fiction. The Doctor is not an intellectual. He never plans anything; he rushes into situations that he's grossly unprepared for and trusts that he'll come up with something. He refuses to carry a weapon despite running into literally hundreds of situations where a weapon would be very helpful. He solves problems with sudden inspiration or intuition rather than logic. He refuses to use consequentialist ethics; he won’t harm a Dalek, or an insane Time Lord who means to destroy the Earth. Any sufficiently advanced intellect is indistinguishable from magic; the Doctor is magic.

The keys to the Doctor must be those ways he diverges from the pattern: his lack of Sherlockian angst, the magical way the universe's coincidences accommodate his lack of planning (rather than disrupting his plans, as it does most protagonists), his God-like status as protector of humanity and the universe, and most especially his embracing of conventional morality and virtue ethics over reason. Like a traditional detective, he holds up our culture for inspection. (This is why he spends so much of his time on Earth, rather than exploring new worlds, as is more common in science fiction.) But he doesn't represent the logical, as Sherlock does. He represents the authors', and the audience's, ideal, the supra-logical God who has the right to judge humanity. He's a Christianized Sherlock Holmes. He still functions to reassure us that our foolishness is wisdom. Not by contrast with it, but as the Platonic ideal of it.

My memory of R. Daneel Olivaw is dim, but those stories certainly weren't meant to reassure us about conventional morality. Humans were inferior to robots intellectually and morally. I think that Asimov was inverting the mystery narrative to fit it to the science fiction narrative: Knowledge is not bad, but good for us. The traditional mystery says logic and humanity are opposed, presumably because humanity is spiritual. Asimov's stories say logic and humanity are opposed, because humans are stupid. Robots are more logical and as a consequence more "spiritually" developed.

While looking up the other Dupin stories in a Poe anthology, I discovered that the version of “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” I was using was a bastardization, a simplified and much-expurgated version written for a schoolbook. It omitted a long introductory essay in which Poe himself spelled out the key to Dupin.

Dupin is a misfit, yet his powers of reasoning are idealized. Dupin fails to validate our conventional lackluster intelligence by being gloomy, because Poe refused to admit that scientific analysis was useful!

That first essay contrasted chess with whist. A second essay in “The Purloined Letter”, given by Dupin rather than by the narrator, said the same thing, only instead contrasting math with poetry. In it, Poe tried to re-purpose both the words “abstract” and “analysis”, to exclude mathematics and to include… poetry. It sounds preposterous, but he was quite explicit about it, and at great length.

Poe attacked chess and mathematics as developing abstract skills that are useless for everyday life. It's a bit confused, since he used the word “abstract” to mean what we would call the real and concrete, calling real life abstract, as opposed to mathematics. He considered logic to be a system that could be applied to either kind of entity, and said it was useful for life only when applied to “abstract” (concrete) entities. This implies deep misunderstandings of both mathematics and logic. Yet its conclusion, that logic can apply to all of life, is closer to truth than is the standard narrative of artists, which assumes just the opposite (that math is strictly abstract, while ordinary life is strictly concrete and cannot be represented in mathematics). In its particulars it is most similar to Aristotle’s position, which was that numbers are all well and good if you want to build a boat, but isn’t really logic.

A small excerpt from Poe’s second essay:

“You are mistaken; I know him well; he is both. As poet and mathematician, he would reason well; as mere mathematician, he would reason well; as mere mathematician, he could not have reasoned at all, and thus would have been at the mercy of the Prefect.”

“You surprise me,” I said, “by these opinions, which have been contradicted by the voice of the world. You do not mean to set at naught the well-digested idea of centuries. The mathematical reason has long been regarded as the reason par excellence.”

… “The mathematicians, I grant you, have done their best to promulgate the popular error to which you allude, and which is none the less an error for its promulgation as truth. With an art worthy a better cause, for example, they have insinuated the term ‘analysis’ into application to algebra…. I dispute the availability, and thus the value, of that reason which is cultivated in any especial form other than the abstractly logical. I dispute, in particular, the reason educed by mathematical study. The mathematics are the science of form and quantity; mathematical reasoning is merely logic applied to observation upon form and quantity. The great error lies in supposing that even the truths of what is called pure algebra are abstract or general truths. And this error is so egregious that I am confounded at the universality with which it has been received. Mathematical axioms are not axioms of general truth. What is true of relation—of form and quantity—is often grossly false in regard to morals, for example. In this latter science it is very usually untrue that the aggregated parts are equal to the whole. In chemistry also the axiom fails. In the consideration of motive it fails; for two motives, each of a given value, have not, necessarily, a value when united, equal to the sum of their values apart. There are numerous other mathematical truths which are only truths within the limits of relation. But the mathematician argues from his finite truths, through habit, as if they were of an absolutely general applicability—as the world indeed imagines them to be…. In short, I never yet encountered the mere mathematician who would be trusted out of equal roots, or one who did not clandestinely hold it as a point of his faith that x squared + px was absolutely and unconditionally equal to q. Say to one of these gentlemen, by way of experiment, if you please, that you believe occasions may occur where x squared + px is not altogether equal to q, and, having made him understand what you mean, get out of his reach as speedily as convenient, for, beyond doubt, he will endeavor to knock you down.

“I mean to say,” continued Dupin, while I merely laughed at his last observations, “that if the Minister had been no more than a mathematician, the Prefect would have been under no necessity of giving me this check. I knew him, however, as both mathematician and poet, and my measures were adapted to his capacity, with reference to the circumstances by which he was surrounded."

Edgar Allan Poe. Essential Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe (Kindle Locations 6981-7013).

What Poe was trying to do with Dupin, then, was make a pre-modernist argument, the precursor to the mystery narrative. The mystery narrative tries to deal with the evident fact that scientific analysis produces much knowledge that makes us intensely uncomfortable by making a sort of “separate magisteria” rebuttal: The detective can use scientific analysis to solve crime, but not to solve his own life problems.

Poe’s mystery, written in 1841, tries to deny that quantitative analysis is analysis, or that it produces anything useful. The Sherlockian narrative is a Hegelian dialectic between conventional and scientific thought. Poe meant his Dupin stories as a last-ditch defense of conventional thought against mathematics and the scientific method, using instead psychological analysis and intuition. I did not expect this, since he published another mystery at the same time, “The Gold Bug”, which was largely mathematical.

Next Chapter: Review- The Clockwork Muse, by Colin Martindale 1990 Estimated time remaining: 40 Minutes