Blog posts

by Bad Horse

Chapters

- The geography of story

- The Urban Fantasy Anthology

- Review: The Hobbit

- Story structure: A Canterlot Carol

- 2012 in review

- Mask of the Sorcerer: Too much wonder

- Clarion Writers' Workshop, and a fimfiction scholarship

- Writing: Jack Bickham, my strange hero

- Writing: Show and tell, part 1: Francine Prose

- Show & Tell 2: Extreme telling

- What not to write, and breaking rules

- On Moving On

- Story recommendation: Biblical Monsters

- Do writers get better?

- Raiders of the Lost Ark

- High-entropy writing

- The Firefly effect

- Review: The Elegance of the Hedgehog

- Art is hard

- Take bad advice

- Art in context

- Setting

- Double Rainboom

- Bronycon

- On Mary Sues

- Why We Read

- I write like...

- Lead your readers

- Pacing

- The 8 Creepiest Things About My Little Pony

- Making story art with the GIMP

- Axe Cop

- Scene structure cures dialogue dysfunction

- Follow each chain of thought to its end

- Writing: Culture & sentence length

- Writing: Plot in Cormac McCarthy's "All the Pretty Ponies"

- Writing: "All the Pretty Pony Princesses" vs. Charles de Lint: The conscious vs. the subconscious

- Why fan-fiction does twists better

- Writing: Compleness in stories, poems, and songs

- Torn Apart and Devoured by Lions

- Writing: Telling vs. body language

- Beyond Ponies

- Writing: When only to show

- When to show & when to tell

- Writing: Show us the theme

- Write-off: Yay me!

- Write-off: Why I love "The Ponies we Love"

- Writing about rape, again

- The annihilation of art

- Structure: Scene+sequel

- CYOA and Moments

- Thoughts on listening to Mahler

- Speech tags: Results

- As I Lay Dying

- Review: Ivan Turgenev's Rudin (1856, Russian)

- Writing: Buildups and resolutions

- 50 questions

- EM Forster on character: Tell, don't just show

- EM Forster, chapter 6: Fantasy

- forster 7 prophecy

- From sadfic to literature

- Saul Bellow's short stories

- "Dark" means pessimistic

- "Dark" means scary / gritty / gruesome

- I am not a serial killer

- Post-modern dialectic as improv

- testing

- Love

- Magica Madoka

- Thursday thoughts: My Princeton interview

- Anonymous Dreams comments

- Brooks & Warren on Showing & Telling

- Pixar's Inside Out

- The Mystery of Mysteries

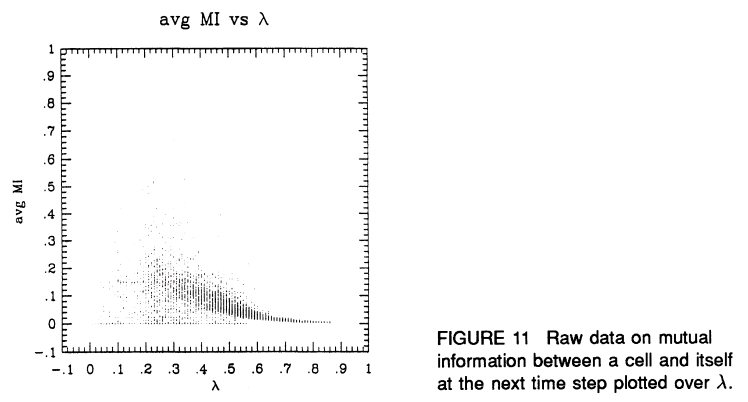

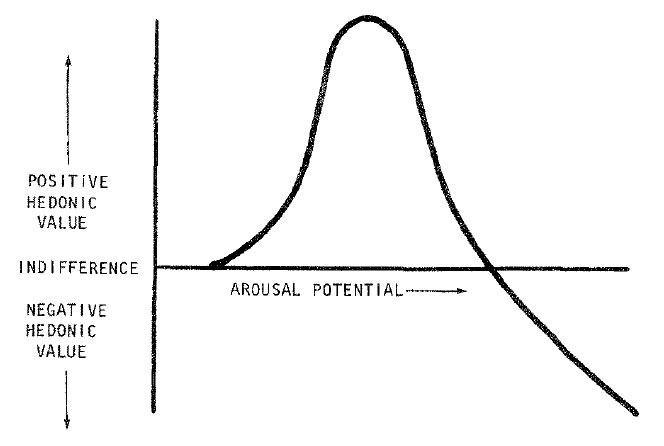

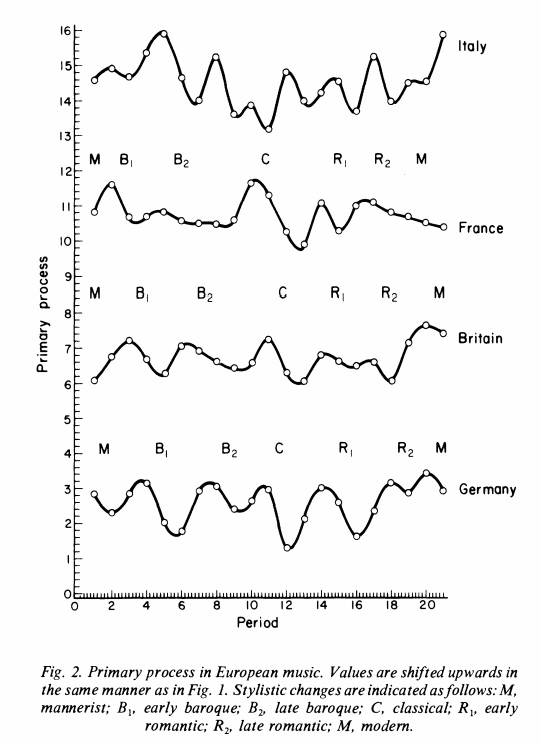

- Review- The Clockwork Muse, by Colin Martindale 1990

- Masochistic weightlifters

- 77. The history of show, don't tell

The geography of story

Screenwriters John August and Craig Mazin said something interesting in their ScriptNotes podcast on Follies, Kindles and Second-Act Malaise: Geography symbolizes story. They didn't say it that way, but John said that one of the things that bothered him about the Broadway play Follies was returning to the same stage sets, and that doing so made him feel like the story wasn't progressing. Craig talked about Star Wars: You can return to a set if it's a vehicle, like the Millenium Falcon, that's going places, and you can return to a set if it has been destroyed to prove that you can't go back (Luke returning to his foster parents' house and seeing their burnt skeletons outside its wreckage).

I immediately came up with counterexamples: Death of a Salesman takes place almost entirely in the family house. The "third act" of Jaws stays on the boat. Night of the Living Dead takes place in one room. So do Rear Window, Wait Until Dark, My Dinner with Andre, and The Breakfast Club. Marty McFly returns over and over again to his hometown in the Back to the Future movies. Characters return to where they started in The Hobbit and Toy Story. My Dinner with Andre and The Breakfast Club are oddities because the "journeys" the characters are taking are not physical. But the others are exceptions that prove the rule.

Death of a Salesman, Jaws, Night of the Living Dead, Rear Window, and Wait Until Dark all have something in common: The people in the story are trapped. The boat, the house surrounded by zombies, and the apartments are all death traps. The characters in Death of a Salesman are trapped in the house by the mortgage and the refrigerator payments, just as they're trapped in their small lives by Willy's deluded faith in the power of friendship and of being liked. The characters return to or stay in the same scene to show that they're trapped.

Marty keeps returning to his hometown, but in different time periods and alternate universes, so that it's a strange and alien place. The changes he discovers in it are the plot. The Hobbit and Toy Story have triumphant returns, where the victory is for the protagonists to be able to return, and to show how much they've grown after doing so.

Maybe screenwriters think about this consciously. I never have. Is this real? Is it important? Can you come up with examples of great stories where movement between physical locations does not symbolize the movement of the plot?

The Urban Fantasy Anthology

The Urban Fantasy Anthology

ed. Peter Beagle, Joe Lansdale

Fiction is usually about people. Mainstream fiction is nothing but character studies; genres are characters plus something else. A mystery isn't about a mystery; it's about a detective: Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poroit, Monk, Sam Spade, Mma Precious Ramotswe—they're all outlandish, fascinating characters, and most readers remember them long after they've forgotten what the mystery was. Horror is about emotion, and life, and our true fears. Comedy is about character, as any stand-up comedian can tell you. And romance—well, the stereotypical Harlequin romance is more like characters minus: Characters with everything but their love relationships played down or stripped away.

But fantasy and science fiction are funny.

As a writer, you'll be told that all stories, even science fiction stories about sentient wristwatches and fantasies about talking ponies, must really be about the emotions of early 21st-century humans. I believe this less than almost any other author, but I break this rule less than most genre authors.

Most authors don't think they're breaking this rule when I think they are. That's because they have a different opinion of what "about" means. They think that "about X" means "the story contains X". I think that "about" means "the story makes me feel X or think about X".

I might write a story where someone drives a car, flies a kite, and whittles a carving. That wouldn't mean the story was about driving, kites, or whittling. In the same way, just because a story has people in it doesn't make it about people. Suppose a monster in a horror story chases two people, and they run away, and one of them makes it and the other doesn't. What is the story about?

If the story makes me feel their horror, then the story is about that fear. But what if it doesn't? What's it about then?

Nothing. The story isn't about anything to me, because it doesn't make me feel and it doesn't make me think. It doesn't matter how many zombies and beheadings it has, it isn't about anything.

The funny thing about fantasy and science fiction is that it's especially easy to unwittingly write a story that isn't about anything. You can flash dragons and unicorns or ray guns in front of the reader, and hope that each time you do that, it tugs on the emotions that each of those things were connected to by the real stories about dragons and unicorns and ray guns that your readers read in the past. You can pile so many of these trappings on that you don't notice your story isn't about anything.

You can even become famous and win awards doing that. Literary types these days are keenly attuned to style. All the stories in this book are written with a mastery of style that makes me salivate with lust and hunger. But style is not enough.

The Lord of the Rings takes place in a fantastical world, but it is only secondarily about that world. You can write a good fantasy that is primarily about a fantastical world, like Dune. And I think you can write a good science fiction story that is primarily about technology or sociology, like Last and First Men (though these are exceedingly rare). What is much more common is for writers to think they're doing that when they're just rehashing old ideas and worn-out trappings that don't make you think. And if the story doesn't make you think and doesn't make you feel, it isn't about anything.

The Urban Fantasy Anthology contains only stories by recognized masters of that vague genre genre. And I'm going to use it to explain what I mean, by telling you which of these stories I think are about something, and which aren't.

Stories that are about something

"A Bird That Whistles", Emma Bull

This story is about a faerie (the old, dangerous kind) who loves to play the fiddle. His love for the fiddle brings him into close contact with humans, and he can't help but observe and be puzzled by love and friendship. The viewpoint character loves a woman, and she loves the faerie, and the faerie loves no one and doesn't know how. The story is about what love and friendship are, and why we love the wrong people, and the unfairness of life, and the power of music.

"The Goldfish Pool and Other Stories", Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman writes a hopefully-fictitious story about himself, going to Hollywood to write a screenplay. Everything happens in a haze, with a continually-changing cast of studio executives whose titles and real authority are never clear, none of whom ever read any of the scripts or summaries that he writes for them. Story decisions are made by the executive's assistants. Meanwhile, he forms a kind of friendship with an old hotel employee, who likes to talk about the movie folks who used to stay there back in the day, back fifty and sixty years ago, and the grandness of character they had.

The story is about a lot of things. Mostly, what people value, and what they give up for it. The old man who cleans the pool is the only man in Los Angeles not trying to play the game. Neil tries to play the game, but finds himself distracted by the germ of a story, a real story that he can write down and tell to people without butchering it for ignorant executives whose only reason for mangling the story is to prove that they're somebodies. The virtuous, contented old man dies and Neil leaves, and the Los Angeles game goes on. It's a little simplistic and moralistic, and I don't understand why the old big movie stars are being held up as anything different from today's big movie stars. But Neil's choice to leave isn't easy, so the story is still about something.

"Hit", Bruce McAllister

God hires a hit-man to kill a vampire who's the son of the Devil. In exchange, God will forgive him everything. Or at least that's what the angel offering the deal claims.

The story has some mystery, and some tension, and some violence. But it's about this hit man and how he feels about what he does, and about selfishness, love, and grace. It's a hell of a story.

"The Bible Repairman", Tim Powers

Torrez has a special kind of soul—one that he broke himself. This makes him valuable to the witch-doctors who can use pieces of his broken soul or vials of his blood for their magic. His sould is doomed to hell anyway, so he thought he might as well sell it off bit-by-bit, until he loses his mind.

But he has stopped. He's trying to hang on to what he has left of his soul and his mind. Then someone comes to him with a plea for help, a chance to save a real live girl. He brings as a gift the stolen soul of Torrez' own little girl. This gift does not have its intended effect, as Torrez is more interested in reconnecting with the ghost of his daughter than in doing the job. But he can't reconnect; the ghost is just a ghost, empty and selfish, not worth saving. And he feels he, too, is empty and not worth saving, and he goes to his death to save the stranger's daughter.

This is a puzzling story, but it makes you think. It is about selfishness, relationships, duty, and identity.

Stories that might be about something

Then we have the stories that are like modern art: You look at them and you know that they might be too deep for you to understand, or they might be con-jobs, and you can't tell which.

"Make a Joyful Noise", Charles de Lint

Zia and her sister are crow spirits, or something like that. They are ancient and powerful and witless and generally well-intentioned, if not overly concerned about mortals. Zia helps the ghost of a boy resolve his issues with his mother and move on, to whatever comes next.

There are stories within this story. The boy's story is about how children can fail to understand their parents' love, and how parents can fail to express it. I have a suspicion the story about Zia might be about something too, though I can't tell what.

"On the Road to New Egypt", Jeffrey Ford

Maybe it's about how religious people take themselves way too seriously, and whoever the forces are behind this world, they're probably jerks. Maybe it's about how Good and Evil, saints and demons, have a lot more in common with each other than with ordinary folk. Or maybe it's just the result of too many drugs.

"Julie's Unicorn", Peter S. Beagle

Julie finds a unicorn in a 500-year old tapestry, captive to a knight and a maiden. She feels so sorry for it that she calls on her grandmother's magic and lets it out of the tapestry. But it remains tiny, and she finds herself its custodian.

The unicorn wants something. She and her ex-lover, who was involved by chance, puzzle out that the unicorn is looking for a monk, who must be in the tapestry. They return it to the tapestry, but into the care of the monk, almost hidden in one corner.

Like many Peter Beagle stories, it's hard to say what the story is about, but I have the feeling that it's about something.

"Companions to the Moon", Charles de Lint

A woman thinks her husband is cheating on her. She follows him, and discovers he has a secret life as a prince of Faerie. The old, dangerous kind. Now that she knows, he must leave her.

Maybe the story is about trust? It would have been an indictment of the woman, if it had been written 400 years ago. But the modern author is, if anything, accusing the man of keeping secrets. Maybe it's about how you can know someone for years, and suddenly find a side of them that you never knew existed.

"On the Far Site of the Cadillac Desert with Dead Folks", Joe Lansdale

A nasty, vicious, vulgar criminal is chased by a slightly-less-nasty bounty hunter, in a world where zombies are a commodity. He captures the criminal, then they're both captured by some weird religious cult that wants to kill them. They agree to work together until they escape. They do. Then they kill each other. The end.

Maybe this story is about how even the most vile, selfish people can have a code of honor. I don't know. It's well-written, but I don't know if there's anything more to it than an adventure story with a couple of revolting yet fascinating protagonists fighting zombies and dominatrix nuns.

Stories that aren't about anything

Finally, sadly, we have the stories that aren't about anything. They have plots and witches and stuff, and they may combine them in new ways, but they don't touch on anything deep or controversial, they don't suck you in and make you identify with a character, and they don't have introduce any new genre trappings novel enough for that to be interesting on its own.

"A Haunted House of Her Own", Kelley Armstrong

In this story, Nathan and his wife Tanya buy a "haunted" house in order to renovate it and charge tourists high prices for staying there. But the townsfolk believe the stories about the house, and Nathan finds increasingly-convincing evidence that the haunting is real. He finally dies in a construction accident. The townsfolk assume it was the ghost. We then discover the whole thing was a scheme of Tanya's to kill her husband.

So what? We can't feel Nathan's fears, at least not after finishing, because we find out that his fears were the wrong ones. We can't feel anything for Tanya. And there is nothing very interesting about a scheme to kill a husband by blaming it on a ghost. I'm not saying it's about nothing because there was no ghost. I'm saying it's about nothing because the author thought that having spooky events and a plot and a twist made it a horror story.

"She's My Witch", Norman Partridge

Boy and girl are lovers. They take revenge on the school bullies. Who murdered him. He's dead, you see. She's the witch who revived him. They plan to go back to school. The end.

"Kitty's Zombie New Year", Carrie Vaugn

Kitty's new year's party is crashed—by a zombie. Not a brain-eating zombie, but the real thing, a woman whose ex-lover damaged her brain with drugs he ordered on the internet, hoping to stop her from leaving him. The zombie confronts him, kind of. His crime is exposed. The police take him away. The end.

You could say this story was about love, and what you might do to keep it. But it isn't, because it doesn't make you think about those things. Maybe he loved her? But the reader never thinks, "Gee, I see his point. I see how, in the same situation, I might do that." The reader never sympathizes with him, and can't very well identify with the zombie. The whole horror/zombie/supernatural angle was just a really long, convoluted way of saying "He abused his woman to make her stay," and the reader condemns him and approves as the police take him away.

"Boobs", Suzy McKee CharnasA woman is taunted by male school bullies who want her body. She becomes a werewolf. She pretends to be willing to have sex with them, then eats them. She enjoys it. The end.

"The White Man", Thomas M. Disch

A little girl from Africa is taught by a lunatic that white people are vampires. Jesus was the first vampire. She knows about vampires from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Eventually, she kills a white man, who may or may not have been a vampire. The innocent? man's death only strengthens the community's belief in vampires, since the death was a thing that happened. The end.

If anything, the story is about how stupid people are, and how insane beliefs can seem perfectly reasonable. Mostly, though, it was a "What the hell?" story. Why did the white man in the story put creepy vaguely-racist messages in his window? What was the point of having the girl's school exploit her to hand-write scam letters?

"Gestella", Susan PatwickA woman is a werewolf. She marries a man who only wants her for her body. She grows old as quickly as a dog. After a few years with him, she is old. He takes her to the pound to get rid of her. The end.

The story is supposed to be about how sad it is that some men don't value women when they get old. Yes, that's sad. But I couldn't identify with her, since it was obvious almost from page one that her husband didn't love her. When you find yourself screaming repeatedly at a character, "Don't go into that basement!", it makes you more aware that they are not you, and destroys identification. Then the story can't be about feeling what they're feeling.

So we're left with the story trying to be about the fact that some people are jerks. But I already knew that. A story where a jerk behaves exactly as you expect him to behave isn't about the fact that some people are jerks, like a story where a fire hydrant works as expected isn't about fire hydrants.

You might notice I listed only five stories by women, and four of them are stories where either a man kills his lover or a woman kills her lover, and I put all of those in the "not about anything" category. Maybe I don't appreciate these stories because I'm a man, and I just don't relate to the whole vengeance-for-treating-me-that-way thing. I don't know. I just call 'em as I see 'em.

Review: The Hobbit

On Saturday morning, I saw The Hobbit, in the company of about a hundred Tolkien fanatics. We discussed it before and afterwards. If you've read the book, there are no spoilers here.

There were some new humorous touches. (Four words: Mini goblin zipline stenographer.) Did they throw something more dignified away in order to get laughs, like Lucas did when he had Yoda fight a comical light-sabre duel? LotR has a grand tone that might suffer from slapstick and silliness. But I think it's okay to have some silliness in The Hobbit. The "crack the dishes, smash the plates" song was silly to begin with, and it was wonderfully choreographed--I wonder how many takes they did and how many dishes they went through.

The changes made were mostly difficult story trade-offs. The way Bilbo left the Shire is an example. In the book, Gandalf and the dwarves bullied/tricked him into leaving, by saying he looked "more like a grocer than a burglar". He got upset and said he'd make a great burglar, and suddenly he found himself leaving with them, befuddled about why he had done so. This was so it could have an arc at the beginning when Bilbo is very foolish, and you don't trust Gandalf, and you feel frightened that Bilbo may have fallen in with a bad crowd. Not all of this would work in the movie, since everyone seeing it has already seen Gandalf in the LotR movies, and won't even think about distrusting him. In the movie, Bilbo is not upset by the grocer comment but agrees with it, and makes a long, deliberate decision to have an adventure. This highlights the Baggins / Took conflict within Bilbo better than in the book. It also starts Bilbo's character arc further along; he is already mature and not easily manipulated. This is all done so that we can spend less time on Bilbo, and more time on Thorin and battle scenes.

Many changes were, IMHO, an improvement. The scene with the trolls was clever. I think Tolkien hadn't decided how powerful Gandalf would be when he wrote that scene, so he showed Gandalf as perhaps not powerful enough to confront the trolls, and using trickery instead. It was a great scene in and of itself, but stuck out horribly when later on Gandalf is much more powerful in battle. The fanatics and I had already went over the 4 possible ways of handling this scene proposed by "Riddles in the Dark". I said all of them were bad: The original way was bad (Gandalf too weak), having a long battle would be bad because there were already too many battles, Gandalf just blasting them with magic would be boring, and the trolls just being stupid would be deus ex machina. In the movie, they gave Bilbo the cleverness instead. This was rushing Bilbo's character arc a little, making him too clever too soon, so that we can spend more time on Thorin and battle scenes. But I can't think of any better way of handling the scene.

They made Radagast into an interesting character, and added a lot of movie time showing him and his animals which I found entertaining. The riddling scene was especially well-done, introducing Gollum's split psyche earlier than Tolkien did, and in an entertaining yet frightening way.

I'd never have understood some of the details my more-fanatical friends did. It seemed bizarre when Gandalf mentions the blue wizards, "whose names I cannot remember at the moment." There are 4 other wizards, whom he's known for thousands of years, and he can only remember the names of two of them? That was a dig at the Tolkien estate, who wanted to charge the movie producers considerable extra to license the material in Unfinished Tales, which is the only place where their names are mentioned. I also wouldn't have known about Figwit, who has a slightly-larger role in this movie.

The only nonsensical big change I noticed was when they held a White Council mini-meeting in Rivendell on Gandalf's arrival. That is a major fail in three ways: It means Gandalf has no reason to leave the dwarves to attend the White Council; they didn't invite most of the members; and it makes no sense, since no one knew Gandalf was coming, not even Gandalf.)

Writers always tell would-be authors to read a lot, but they never tell them to watch movies. Watching movies is important for writing! Movie directors are better at thinking cinematically than writers are. See enough movies that you get a sense for the cinematic, and that how something is seen, camera angles and lighting and all, pops into your head while you're writing. There's a scene where Bilbo walks through his silent, empty home in the morning, deciding whether to go or stay. There's a scene where he sneaks up behind Gollum, meaning to kill him, and sees the terrible misery in Gollum's face, and spares him. There's a scene where the dwarves gather around the fireplace and sing that sad song about their home. If you didn't have pictures in your mind, you'd have a hard time describing in words what happened and why.

The songs, BTW, were well-done. I love the melodies in the old Rankin-Bass version, and even the songs Tolkien didn't write, like "The greatest adventure" and "Where there's a whip, there's a way". (I know Tolkien die-hards hate them because of their modern sound. Bite me.) But the melodies in this one are good too, though I was disappointed that they cut "Fifteen birds in five fir trees" (due to the need to rewrite the story to change it to a battle scene that rushed Bilbo's character arc and his reconciliation with the company).

The "mistakes" that I predicted were adding more battles and making the existing battles bigger and longer. There's a long battle flashback added to provide Thorin's motivation, which I would like to have seen summarized in a few lines of dialogue, but that's because I think the movie is about Bilbo, not Thorin. It was wrong for the tone of the first half of The Hobbit. The book opens pastorally, and I like that. I like some time spent travelling across the wilderness, feeling the bigness of it, slogging through the mud between sudden and dramatic fight scenes. This movie doesn't do that.

That's a problem with this Hobbit: Too many battle scenes, and too many characters spending too much time hanging over precipices. It has the pacing of an action movie. The action segments were overdone and unbelievable. The long, LONG fight scene inside the goblin mountain was so ridiculous, I had to look away--what with each dwarf killing dozens of goblins, despite being outnumbered about a thousand to one, and falling hundreds of feet onto rock with no ill effects, not once, but twice--that's twice per dwarf--I felt I was watching the Keystone Kops. Thorin uses a ladder as a shield against archers, and all their arrows conveniently lodge in its rungs. Later, they're caught in five or six devastating rock slides and crushed between two mountains slamming against each other, but no one is injured. That's the level of ridiculousness. I can't fear for these dwarves anymore; they're obviously made of dwarfonium.

(My fanatical friends did not mind the unreal fight scenes, but were upset at the implied rate of travel possible over the Misty Mountains via bunny sled. This probably says something about the geek psyche.)

The other problem with this Hobbit is that Bilbo peaks too soon. We've only gotten to the end of the first movie, and he's already become heroic and finished his character arc (in an added, unrealistic fight scene). I said this to someone else in the group, and he thought that Peter Jackson didn't think The Lord of the Rings was about Frodo; he thought it was about Aragorn. Likewise, Jackson probably thought The Hobbit was about Thorin.

That does explain a lot about Jackson's version of LotR. Still, I laughed at the idea that anybody would spend hundreds of millions making a film of a book called The Hobbit and put it in the hands of somebody who thought the story was not about a hobbit--until someone read out loud part of an interview with some of the development team, who said that The Hobbit was really Thorin's story. Ugh. Hollywood.

I kept being struck by how much Tolkien re-uses the same themes and plot elements in the Silmarillion, the Hobbit, and LotR. He plagiarizes from himself. This didn't bother me as much in the books, which were about Bilbo and Frodo, who are strong enough characters to carry a book. But with the movies instead being about Thorin and Aragorn, neither of whom are interesting enough to support one movie let alone three apiece, the similarities start to annoy me. The Arkenstone, the rings, the Silmarils--they all serve similar story functions. Bilbo and Frodo are variations on a theme, as are the company of dwarves and the Company of the Ring. I don't even remember how many kings seeking to restore their kingdoms Tolkien has. He has two dwarven kingdoms carved out under a mountain that the dwarves were driven from after their riches attracted enemies.

One good thing about highlighting Thorin early on is that it fixes one of the book's major failings. The book opens with the dwarves being nasty money-grubbers who are all about the gold, and around chapter 10 it drop-shifts into being a king's quest to reclaim his kingdom. The movie introduces the king's quest right off the bat.

At least Thorin isn't as dull a character as Aragorn becomes once he leaves the Shire. This raises the issue of character flaws. You might think Aragorn is dull because he has no flaws. I've said on this blog that writers who tell you to make your characters interesting by giving them flaws are wrong, and I stick by that. Aragorn is dull because he speaks and acts the way we expect noble warrior kings to. Gandalf, on the other hand, also has no serious flaws--you could even accuse him of being a Mary Sue, if he weren't absent so much of the time--yet he is a very interesting character. He just has his own way of doing things. You don't need flaws to make a character interesting.

We discussed what it meant to the story for Thorin to be young instead of old. Most of us thought it was just to draw women to the movie--I asked why they couldn't have made one of the dwarves into a hot babe for my sake, then--but someone turned up an interview with someone on the development team who said it was to allow Thorin to fight more energetically. IMHO, a key consideration is how it makes you feel when Thorin presumably dies in the end. In the book, Thorin's death was sad, but, honestly, the guy was pretty old already, and so instead of being a tragedy, it was more of a "circle of life" moment, and an "at least he saw his home again before he died" moment. If this young Thorin dies at the end, it will change the tone of the story.

Story structure: A Canterlot Carol

When you read GhostOfHeraclitus' new story, "A Canterlot Carol", you might imagine that he wrote it in a mad dash of inspiration, like Coleridge writing the opening to "Kubla Khan". He did in fact write almost all of "Twilight Makes a Cup of Tea" that way, only under the influence of some particularly-nice tea (I assume) rather than opium. But I have an inside line on ACC, so I can point out some of the deliberate story structure choices.

Let's look at an outline of the story. SPOILERS EVERYWHERE.

Scene 1: Dotted's office.

Humorous opening with Santa Claus

Scene 2: Spinning Top's office.

Continuation of Santa Claus humor

Introduction of Zebra / Blueblood subplot

Dotted insists that Spinning goes home for Hearthwarming with her family

Dotted has plans for Hearthwarming

Scene 3: Zebrican embassy.

Heightening of tension over meeting Mkali

Discussion of the meaning of Hearthwarming

Vital discussion of the economics of Zebrica-Equestria trade relations

Dotted has plans for Hearthwarming

Scene 4: Dotted's office.

Dotted insists Leafy goes home for Hearthwarming

Dotted has plans for Hearthwarming

Scene 5: Dotted's office.

Dotted's plans for Hearthwarming are to work at his desk so everypony else can go home

Dotted is lonely and sad even though he won't admit it to himself

Scene 6: Celestia's study.

Celestia also missed Hearthwarming because she was doing Dotted's work for him just as he was doing that work for the other ponies

Dotted puts a blanket over her, takes the paperwork, and returns to his office, re-invigorated by the Princess' example, its proof of his importance to her, its vindication of his own actions, and his ability to be useful and repay her love

Nice Christmas colors, Bad Horse!

They are nice, aren't they? They are about Christmas, because the story is about one meaning of Christmas. But they're also color-coding the story. Elements that address the story's theme are green. Elements that grab the reader and string her along between the green bits are red.

Neither of us were able to think of a subplot introducing the theme that was short and funny enough to open with, so he came up with the Sandy Claws opener, which is funny, short, and doesn't set up any distracting expectations. After that hook, almost everything in the story derives from the theme, which is told in scene 3, discussion of the meaning of Hearthwarming, and shown in scene 6. GOH came up with a "plot" revolving around the Zebra ambassador because she, an outsider, can ask what the meaning of Hearthwarming is. GOH threw out some earlier plots because they didn't directly contribute to the theme, and because they set up a conflict and an expectation for a confrontation with the antagonist and a resolution of that conflict, which would have derailed the story. He changed Dotted's "meaning of Hearthwarming" explanation from what it was previously (more in line with standard Christmas theory) to what it is now so that it made his story's theme clear:

"I guess you could say it is about being thoughtful. A reminder to not only love, but to be mindful of that love, and to be grateful for having somepony to share it with."

The tension with Mkali is just long enough to create some tension and drag the reader along, then be defused before the reader's forgotten about the true conflict driving the story, which was planted in scene 2: Dotted wants to make sure everypony else gets home for Hearthswarming. We immediately return to that in scene 4 with Leafy, and from there on it's all theme, all the time, until the clincher at the end, repeating the refrain Dotted has been repeating throughout the story, which was first optimistic, then tragic, and is now triumphant.

THIS IS WHY I LOVE THIS STORY.

Bonus meta-rant: See, analyzing something doesn't ruin it by taking away the mystery! It makes it better.

2012 in review

I'm stealing bookplayer's Year in Review questions. This is mostly for my own benefit.

Fic total:

29 stories and about 90,000 words, depending how you count.

Overall impressions:

It's much more fun to write when you can immediately find out how many people read your story and how many of them liked it, read their comments, and even get to know some of them. If you guys hadn't read, liked, and commented, I wouldn't still be here.

It's also much more informative. For the first few months I broke my stories up into short chapters and watched the view count on each chapter to find out where people stopped reading. (Half of readers stop somewhere on the first page, no matter how short or long it is. 90% or more of those who go on to the second page will finish the story. The critical area appears to be the first 500 words. Grammar doesn't matter.)

And I scan the other stories on the site, and see how popular they are, and learn what readers like. Writers have never known this stuff before. Nobody knows how many or what kind of stories editors reject or how many people read each of the different stories published in a magazine, and while we have sales figures for books, they're so distorted by the different amount of marketing power put behind each book as to be meaningless (unless you know the marketing budgets as well!)

I've told this to other writers, but most scoff. I went from being afraid my family would see my fanfic, to telling them how to find it, to asking them to read it, to no avail. People outside fandom won't touch it, with few exceptions.

TL;DR: Fanfic is my secret weapon in my competition with the other writers of the world. Not because I keep it secret, but because they won't listen.

Looking back, did you write more fic than you thought you would this year, less, or about what you'd predicted?

I didn't mean to write fanfic at all. I still don't. I meant to write television scripts. Somehow one pony story became two, became three, and so on. I was surprised that I could write 70,000 words of final draft in half a year of weekends when I was trying not to write.

What pairing/genre/fandom did you write that you would never have predicted in January?

My Little Pony. Shipping. A bit of Lunestia. (Don't ask. It's bad.)

What's your own favorite story of the year? Not the most popular, but the one that makes you happiest?

The stories that make me happiest are the ones that make me saddest. Is that twisted? I guess favorite story goes to The Detective and the Magician. But favorite moment goes to this exchange from A Carrot for Miss Fluttershy:

DERPY HOOVES hurries on-stage, followed by a COLT and a FILLY.

FILLY AND COLT

Derpy derpy derpy!

Big Mac gives the colt and filly one look and they hurry off.

SCOOTALOO

Were they teasing you because you're a pegasus?

DERPY

Naw.

(her ears flick down)

They always do that.

(to Big MacIntosh)

Why're you sitting in the street?

SWEETIE BELLE

He's mad because Farmer Seed won't sell him a carrot for

Fluttershy because she's a pegasus!

Scootaloo pushes with her helmet against Big Mac's side, trying and failing to budge him.

SWEETIE BELLE (CONT'D)

It's so romantic!

DERPY

You're just gonna sit there?

BIG MACINTOSH

A pony can sit.

DERPY

Because Hay Seed won't sell carrots to pegasus ponies?

BIG MACINTOSH

Eeyup.

DERPY

(beat)

Will that help?

BIG MACINTOSH

Nope.

After a long pause, Derpy sits down beside Big MacIntosh.

I still like that story, though no one else did. Literally. It has zero likes. Equestria Daily Pre-Reader #12 said (paraphrased), "We give stories three strikes before rejecting them completely. But this one is so bad, I'm giving you all three strikes right now."

Did you take any writing risks this year? What did you learn from them?

I tried writing comedy. I thought I'd hate it and be awful at it. It was fun!

Story of mine most under-appreciated by the universe, in my opinion:

Severus Spike. Wow, a lot of people disliked it. Apparently there's an unwritten rule against rewriting scenes from one fandom with characters from another. I can only imagine what they'd think of Borges' "Pierre Menard". I found exploring the parallels and differences interesting.

Most fun story to write:

The Saga of Dark Demon King Ravenblood Nightblade, Interior Design Alicorn

Also the fastest, at 15-20 hours per chapter.

Story with the single sexiest moment:

If I tried writing a sexy scene, it would probably come out like this.

Most "Holy crap, that's wrong, even for you" story:

Twilight Sparkle and the Quest for Anatomical Accuracy.

Story that shifted my own perceptions of the characters:

Detective & Magician, because I disliked Trixie. Burning Man Brony, because the structure forced me to portray all the Mane 6 positively, even the ones I don't like. (Not telling.)

Story I learned the most from:

Fallout: Equestria taught me you can write stories that are both interesting and exciting.

How to Do a Sonic Rainboom gave me a revelation about relating plot and character.

Being a developmental editor for A Canterlot Carol was an education in the connection between plot and theme.

Mortality Report taught me that I need to align the surface associations between what is present, what is happening, and what the characters are feeling, with the deep thematic causal relations between these things (which I failed to do, confusing hundreds of readers).

The Snowpony has the style I wish I could write with.

I don't yet know what I learned from So Be It. It disturbed me a lot. Hopefully I'll yet learn something from it.

Hardest story to write:

The ones that died on the operating-room table (The Real Reason, Moving On, Second-Best Pony), and the ones I rewrote repeatedly and almost gave up on (Mortality Report, Burning Man Brony, Twenty Minutes). Detective & Magician wasn't as intensely painful in any one place, but it took an absurd amount of time. I still can't believe it's only 14,000 words. It felt like writing a novel.

Biggest disappointment:

Trying and trying and revising again and again and still not getting a fresh, poetic style, which some despicable nameless people seem to produce as easily as pissing.

Equestria Daily refusing to read Friends, With Occasional Magic ("Avoid people from the fandom"), Burning Man Brony ("No brony-in-Equestria"), or Twenty Minutes ("No featuring of Fallout: Equestria stories"). Fimfiction not allowing me to publish "A Carrot for Miss Fluttershy" ("No scripts"). Not being able to get "Friends, With Occasional Magic" moved to my Bad Horse account.

Biggest surprise:

Mortality Report and Twenty Minutes. People hated the first, second, and third versions of each of those.

Most Unintentionally Telling Story:

The Saga of Dark Demon King Ravenblood Nightblade, Interior Design Alicorn was, unintentionally, an allegory.

Fanfic Resolutions:

1. Stop writing fan-fiction.

2. Write more fan-fiction.

Mask of the Sorcerer: Too much wonder

I'm going to do something terrible. I'm going to "review" a book by a brilliant writer without finishing it, because I don't think I'll ever finish it. But my purpose isn't to review the book; it's to make a point about writing.

Darrell Schweitzer may be the smartest, most-creative person who's ever written fantasy. I see him as a tragic figure. I've watched him for many years, as he shows up at every science fiction convention on the east coast, aggressively selling books in the dealer's room and in the hallways. I'm his stalker. I'll spend an hour listening to him on one panel (where he will speak more than his "fair" share, which is fair, as he has more interesting things to say than everyone else). Then I'll follow him to another panel and listen to him for another hour, then follow him to the con suite and sit a little distance away in a chair and just listen as he goes on for another hour, pouring out facts and ideas about the Byzantine Empire, Aboriginal petroglyphs, or another funny but tragic story about Philip K. Dick, connecting them all together with reasoning as crazy and yet obvious in retrospect as a Tim Powers novel.

I may be the only person in the world who finds him so fascinating. The other people he talks with more often seem irritated at not being able to inject their ideas into the conversation in the face of Darrell running at full steam. I'm usually the guy crowding other people out of the conversation, but Darrell is one of the few people who is so interesting that I'd rather hear what he's going to say next than to speak my own thoughts.

He works so hard, and he loves fantasy and science fiction. He did many of the best interviews of all the grant masters of the past fifty years, and has collected them in a series of little books called "SF Voices" or "Speaking of the Fantastic", which you can buy from him in the dealer's room of any major science fiction convention between Washington DC, Pittsburgh, and Boston. I've been rooting for him for years, waiting for his breakthrough novel, for him to get the recognition he deserves, but just watching him get older and greyer.

Funny thing, though, is that I never read any of his novels. His short stories, his interviews, his essays, yes. Not his novels. I have a huge reading list, and I never read books unless they're strongly recommended by many people. No one ever recommended his books to me. He hasn't written many; if you search for his novels on Amazon you won't find them, because he's edited so many books--mostly collections of Lovecraft, horror, mystery, and pulp adventure that are not nearly as good as Darrell's own writing.

But when I realized, after posting some unsuccessful ponyfics, that I was an unpopular author because I tried to put too much abstract reasoning into my stories, I wondered if there might be a clue as to what I was doing wrong in Darryl's work. So I bought Mask of the Sorcerer, which he recommended as his best.

It's a little unfair to treat this as a novel, because the first 4 chapters were originally a short story. The novel's main failing is that those first 4 chapters are a complete story, meaning you have little motivation to continue on to chapter 5. But there's more to it than that.

The hero is the son of a magician. They live out over the water on the end of a great pier of an exotic city, which worships and fears the river gods, who are very real. The magician becomes a sorcerer, summoning the dead to mysterious rites in their house at night. He sends his son out into the river among the crocodiles and spirits at night to receive a great vision. The son receives the vision; he returns to find his mother has disappeared and his father will not say how. The sorcerer calls up a great storm which wrecks the city; he dies; the townsfolk burn the house; the boy seeks out the Sybil; the Sybil pronounces his fate; the boy returns home to see his sister stolen away by his father's spirit and to receive a threat from a zombie. The boy journeys down the river of the dead in search of his sister.

That's, like, the first two chapters.

I could go on, but I think you get the point. This book contains too much wonder. Almost every page introduces something new and wondrous and amazing, which recasts the underlying reality of the story world and your understanding of what is possible and what is good. Never at any point in the first four chapters did I have the slightest clue as to what might happen next. Darrell let loose and blasted me with a firehose of fantastic beings and events, and it was too much. Everyone the main character cared about was soon dead or worse, but it wasn't clear how much that even mattered in this world, or whether getting them back was possible or would be a good thing. I had no ground to stand on, no context to use to decide what I hoped would happen.

Ergo, I didn't care what happened next.

The book has wonderful things in it. The theme is something about destiny. The main character doesn't want to become a sorcerer, but can't escape his destiny, which seems to be to become horrible, inhuman, and god-like. But the only piece of firm ground to stand on was the main character's desire to throw off his destiny as as sorcerer and return to his teacher, to learn to copy and illuminate manuscripts. That dream is ripped to shreds in chapter 5. So you're left with a protagonist whose main goal is not do everything that he has to do, and with befuddlement over what you should be hoping for. And, perhaps most importantly, the suspicion that none of this is relevant to you, because the world and the main character's destiny are nothing like your own.

Fantasy can't exist without the mundane. All wonder and no normality is like all Pinkie Pie and no Applejack. Er. Or something.

Clarion Writers' Workshop, and a fimfiction scholarship

I know you guys are all stolid, respectable members of society. But I thought there might be one or two crazy people out there who are into ... dare I say it ... writing fantasy.

If you want to write fantasy or science fiction professionally, you should apply to Clarion. Clarion is to science fiction & fantasy what Harvard is to high-powered law firms and Wall Street sharks, but (sadly) without the evil. Like Harvard, it's a great learning experience, but that's not why you need to go. You need to go because if you send a story or book into a science fiction or fantasy editor, and you write on your cover letter "I went to Clarion", they will read it, or at least some of it. I spent years writing stories and getting dozens of photocopied rejection letters. After Clarion, I sold the first two stories I sent out to the first places I sent them out to. (One of the checks bounced, but that wasn't Clarion's fault.) I haven't seen a rejection letter since. Mostly because I haven't written anything but fan-fiction since. But that's not important. What's important is that if you want to become a professional F&SF writer, you should apply to Clarion.

When I went to Clarion, they put us all up in tiny 2-person dorm rooms with window air conditioners that roared like jet engines, so that you couldn't write, let alone sleep, with them on (because of the noise) or with them off (because of the heat). So Lister Matheson, who ran Clarion at the time, gathered about a dozen standing fans of all different types from the pocket dimension where he always managed to find at the last minute whatever Clarion needed, and distributed them to our rooms. I remember typing stories on a word processor—literally, a machine that was not a computer and did nothing but word processing, with a four-line LED screen—but I have no idea whose it was. Now they tell you to bring your own laptop. They provided a printer.

Once a week, you write a story, print up 18 copies, and hand them out. Each morning you all sit in a big circle and spend 3 hours critiquing about 4 stories, every person giving their opinion in turn. We had the official Clarion Black Stetson Bad-Guy Hat to put on if you thought the story stunk. (I was heavily black-hatted the week that I had no story and instead put my name on the first four pages of the Eye of Argon and handed it out. Don't do this unless you can handle an entire week of covert, frightened glances from your classmates.) Then the instructor gives their opinion, and everyone hands their marked-up copies of the story back to its author and moves on to the next story. Then you have lunch, and return to the dorm to read other people's stories, mark them up with red pen, and work on your own story for next week.

What did I learn? Well, you're getting critiques from other students, so mostly you'll get line edits (grammar, word usage, awkward sentences, wordiness, repetition) and story content reactions (I didn't care about this person, this threat wasn't threatening, this contradicts that, I didn't understand what happened). Seeing critiques of other stories is as valuable as reading critiques of your own stories.

I wouldn't go back to Clarion now, because my problems now are mostly things I do over and over that I'm already aware of, or that require a theoretical understanding of story to fix (bad dramatic structure, unclear theme, competing themes, subtext that contradicts theme, scenes whose relation to the story problem are not immediately clear). Nor could I; you may go to Clarion only once. But my writing post-Clarion was noticeably better than before Clarion.

Perhaps more importantly, I spent six weeks getting to know people who care about the same crazy kind of stories that I do, who can write pretty well (even if most of them scorn my fan-fiction), and whom I'm still in contact with today.

Applications for the 2013 Clarion Workshop will remain open until March 1, 2013. On February 15th, the application fee will increase from $50 to $65. The 2013 faculty will be Andy Duncan, Nalo Hopkinson, Cory Doctorow, Robert Crais, Karen Joy Fowler, and Kelly Link. You must include two complete short stories, each between 2,500 words and 6,000 words in length. No novels, poetry, essays, or screenplays. No word back yet from Karen on whether you can submit fan-fiction.

The workshop fee is, yikes, $5000 (including room & board). It was cheaper when I went. Most people get a scholarship, but the size of the scholarships hasn't increased with the price of tuition; most are still about $1000. Don't bother asking exactly how much; they're a lot of different individual scholarships--little independent bookstores will fund one student, or a regional science fiction convention will fund one person from its state. There are special grants for students of color (I don't which colors count; yellow usually doesn't), students age 40 and older, students who are affiliated with Michigan State University, and students who are affiliated with UCSD.

These are some of the people who went to Clarion before starting their writing careers:

Tim Pratt

Other SF&F Writing Workshops

There is also Clarion West, in Washington State, which is modelled on Clarion. This year, their instructors are Elizabeth Hand, Neil Gaiman, Joe Hill, Justina Robson, Ellen Datlow, and Samuel R. Delany. Application fee is $30 thru Feb. 10, then $40 until midnight of March 10. The workshop costs $3600 (including room & board). Writing sample 20 to 30 pages of manuscript (that's about 5000-7500 words).

Can you submit fan-fiction for your writing sample to Clarion West? Neile Graham says: "They can, but I strongly recommend against it. It's riskier than submitting original fiction, because the tendency of most fan fiction is to rely on the original source for much of the characterization and world-building issues, leaving fiction that isn't as strong out of context, especially for readers not familiar (or not sympathetic) with the source."

Odyssey is also modelled on Clarion. Application fee is $35. Tuition is $1920, textbook $100, optional college credit $550, housing $790, food about $500; total without college credit (not offered at Clarion): $3410. Writing sample maximum 4000 words. Applications must arrive there by April 8. No electronic applications.

Jeanne Cavelos says, "We don't prohibit applicants from submitting fan fiction as their writing sample. But if someone asked my advice, I would advise them to submit something else, since fan fiction probably won't showcase their skills in characterization and world-building."

Both these other workshops also have good reputations. I promise not to think much less of you if you go to a lesser, Johnny-come-lately knock-off of Clarion.

Regarding $$$: A FimFiction Scholarship

Most of the people I'd like to go to Clarion, can't afford to. I'd like us, fimfiction as a whole, to sponsor somebody to attend one of these workshops. Ideally there would be a non-profit escrow fund, like for the Wollheim Memorial Scholarship (which is split among people from the NYC area who are admitted to Clarion, Clarion West, or Odyssey), but for now, making pledges on this blog post would suffice.

I don't want to collect money myself, because I know screaming and accusations would inevitably follow on our lovely little community here. So here's my plan:

- A writer qualifies for the fimfiction scholarship if they were registered for fimfiction as of January 1, and they have at least 2 stories published on fimfiction totaling at least 5,000 words, or 1 story on Equestria Daily, by March 1.

- To donate, post a comment on this blog saying "I will give $X by paypal to fund fimfiction writers to attend these writing workshops if one is accepted," where X >= 5.

- If you are a qualifying writer and you're accepted into a workshop, PM me as soon as you find out, tell me your real name, the workshop you'll be attending, and a made-up secret word, and I'll get in touch with their organizers and verify that you were accepted and you are who you say you are (using the secret word).

- I will get the participating workshops each to set up a paypal account or other method to receive fimfiction donations and list it on their websites (to prove they control those accounts). Neile Graham of Clarion West says that a Paypal account is complicated for non-profits (they have extra paperwork to set one up), but they can arrange something similar.

- I will then post a blog saying who was admitted, where they're going, and how to contribute to their fund. This is not tax-deductible in the US, because you're donating to a specific person rather than to the workshop.

- I, Bad Horse, will match all received contributions up to $250 if we have someone accepted to any of the workshops.

(You can't use a kickstarter campaign to fund a scholarship. I checked.)

Writing: Jack Bickham, my strange hero

Scene and Structure is a good little book by Jack Bickham with several simple formulas that work to keep stories engaging. Jack Bickham wrote many action/adventure/suspense novels, although he's better-known for the columns and books he wrote for Writers' Digest.

But I noticed that Bickham only uses examples from action/adventure novels. He's always talking about car chases, gunfights, and mine accidents. And the prose in his examples is terrible. So I bought some of his novels, to better understand how to interpret his advice. It's not a good sign when you list an author's books in order of popularity, and the top seven are books on how to write books. Those who can't do, teach.

Jack Bickham was in many ways a terrible author. I say this after skimming two of his most-popular novels, Twister[1] and Tiebreaker. His minor characters are sometimes a little interesting, but his major characters always break down cleanly into good guys and bad guys—and the good guys are all basically the same person. (One of Bickham's pieces of advice is to keep the character and motivations of the protagonist and antagonist simple, clear, and free of all shades of gray, so the reader roots whole-heartedly for the protagonist and yearns to see the antagonist crushed. This makes the story less interesting, but it does keep you turning pages, at least for a while.) His stories have no themes worth mentioning. The plots, characters, and dialogue are hackneyed and uninteresting. Yet it's hard to stop reading.

Jack Bickham had very little talent or art. He wanted to write, and he studied long and hard and figured out how fiction works. And that was enough. He didn't have keen observational powers; he didn't have deep insights into human nature; he had no good ideas; he couldn't create complex characters or write poetic prose. He didn't have the gift. But he powered through with brute-force analysis and willpower, and made his living writing stories that entertained people. He's the Daniel "Rudy" Ruettiger of writing, and he actually made it for a while. That makes him a kind of hero to me. Not the kind I want to be, but the kind I have to admire, and who can give me hope of a sort.

[1] Not the basis for the movie Twister, or at least he wasn't credited for it.

Writing: Show and tell, part 1: Francine Prose

Someday I hope to write a longer post on this, but today I need to type in this passage from Francine Prose's excellent Reading Like a Writer, which I recommend you get immediately if you're serious about writing, with the caveat that this is very advanced and dismayingly difficult stuff to emulate and will likely give you nightmares about your inadequacy as a writer.

The opening of "Dulse" by Alice Munro:

At the end of the summer Lydia took a boat to an island off the southern coast of New Brunswick, where she was going to stay overnight. She had just a few days left until she had to be back in Ontario. She worked as an editor, for a publisher in Toronto. She was also a poet, but she did not refer to that unless it was something people knew already. For the past eighteen months she had been living with a man in Kingston. As far as she could see, that was over.

She had noticed something about herself on this trip to the Maritimes. It was that people were no longer so interested in getting to know her. It wasn't that she had created such a stir before, but something had been there that she could rely on. She was forty-five, and had been divorced for nine years. Her two children had started on their own lives, though there were still retreats and confusion. She hadn't gotten fatter or thinner, her looks had not deteriorated in any alarming way, but nevertheless she had stopped being one sort of woman and had become another, and she had noticed it on this trip.

Prose writes:

... Finally, the passage contradicts a form of bad advice often given young writers--namely, that the job of the author is to show, not tell. Needless to say, many great novelists combine "dramatic" showing with long sections of the flat-out authorial narration that is, I guess, what is meant by telling. And the warning against telling leads to a confusion that causes novice writers to think that everything should be acted out--don't tell us a character is happy, show us how she screams "yay" and jumps up and down for joy--when in fact the responsibility of showing should be assumed by the energetic and specific use of language. There are many occasions in literature in whcih telling is far more effective than showing. A lot of time would have been wasted had Alice Munro believed that she could not begin her story until she had shown us Lydia working as an editor, writing poetry, breaking up with her lover, dealing with her children, getting divorced, growing older, and taking all the steps that led up to the moment at which the story rightly begins.

Richard Yates ... Here, in the opening paragraph of Revolutionary Road, he warns us that the amateur theatrical performance in the novel's first chapter may not be quite the triumph for which the Laurel Players are hoping:

The final dying sounds of their dress rehearsal left the Laurel Players with nothing to do but stand there, silent and helpless, blinking out over the footlights of an empty auditorium. They hardly dared to breathe as the short, solemn figure of their director emerged from the naked seats to join them on stage, as he pulled a stepladder raspingly from the wings and climbed up halfway its rungs to turn and tell them, with several clearings of his throat, that they were a damned talented group of people and a wonderful group of people to work with.

When we ask ourselves how we know as much as we know--that is, that the performance is likely to be something of an embarrassment--we notice that individual words have given us all the information we need. The final dying sounds ... silent and helpless ... blinking ... hardly dared to breathe ... naked seats ... raspingly.

This second passage is a mix of showing and telling, or telling disguised like showing. "Silent and helpless" is not really showing--how does an actor look helpless? How does one see that they "hardly dared breathe"? A truly talented group would be described as "talented", not "damned talented"--is that little bit of information showing or telling? This passage illustrates that the important question isn't whether you're "showing" or "telling", but whether you're using the right evocative words, in your narration and your dialogue.

Show & Tell 2: Extreme telling

A Raisin in the Sun, Lorraine Hansberry

Act I, Scene 2

MAMA: You something new, boy. In my time we was worried about not being lynched and getting to the North if we could and how to stay alive and still have a pinch of dignity to... Now here come you and Benetha--talking 'bout things we ain't never even thought about hardly, me and your daddy. You ain't satisfied or proud of nothing we done. I mean that you had a home; that we kept you out of trouble till you was grown; that you don't have to ride to work on the back of nobody's streetcar--You my children--but how different we done become.

Act III, Scene 1

WALTER: Talking 'bout life, Mama. You all always telling me to see life like it is. Well--I laid in there on my back today... and I figured it out. Life just like it is. Who gets and who don't get. Mama, you know it's all divided up. Life is. Sure enough. Between the takers and the "tooken." I've figured it out finally. Yeah. Some of us always getting "tooken." People like Willy Harris, they don't never get "tooken." And you know why the rest of us do? 'Cause we all mixed up. Mixed up bad. We get to looking 'round for the right and the wrong; and we worry about it and cry about it and stay up nights trying to figure out 'bout the wrong and the right of things all the time... And all the time, man, them takers is out there operating, just taking and taking.

.

Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller

Act I

WILLY: Bernard is not well liked, is he?

BIFF: He's liked, but he's not well liked.

HAPPY: That's right, Pop.

WILLY: That's just what I mean, Bernard can get the best marks in school, y'understand, but when he gets out in the business world, y'understand, you are going to be five times ahead of him. That's why I thank Almighty God you're both built like Adonises. Because the man who makes an appearance in the business world, the man who creates personal interest, is the man who gets ahead. Be liked and you will never want. You take me, for instance. I never have to wait in line to see a buyer. "Willy Loman is here!" That's all they have to know, and I go right through.

LINDA: Then make Charley your father, Biff. You can't do that, can you? I don't say he's a great man. Willy Loman never made a lot of money. His name was never in the paper. He's not the finest character that ever lived. But he's a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid. He's not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog. Attention, attention must be finally paid to such a person. You called him crazy--

BIFF: I didn't mean--

LINDA: No, a lot of people think he's lost his--balance. But you don't have to be very smart to know what his trouble is. The man is exhausted.

HAPPY: Sure!

LINDA: A small man can be just as exhausted as a great man. He works for a company thirty-six years this March, opens up unheard-of territories to their trademark, and now in his old age they take his salaray away.

HAPPY: I didn't know that, Mom.

LINDA: You never asked, my dear! Now that you get your spending money someplace else you don't trouble your mind with him.

HAPPY: But I gave you money last--

...

BIFF: Those ungrateful bastards!

LINDA: Are they any worse than his sons? When he brought them business, when he was young, they were glad to see him. But now his old friends, the old buyers that loved him so and always found some order to hand him in a pinch--they're all dead, retired. He used to be able to make six, seven calls a day in Boston. Now he takes his valises out of the car and puts them back and takes them out again and he's exhausted. Instead of walking he talks now. He drives seven hundred miles, and when he gets there no one knows him any more, no one welcomes him. And what goes through a man's mind, driving seven hundred miles home without having earned a cent? Why shouldn't he talk to himself? Why? When he has to go to Charley and borrow fifty dollars a week and pretend to me that it's his pay? How long can that go on? How long? You see what I'm sitting here and waiting for? And you tell me he has no character? The many who never worked a day but for your benefit? When does he get the medal for that? Is this his reward--to turn around at the age of sixty-three and find his sons, who he loved better than his life, one a philandering bum--

HAPPY: Mom!

LINDA: That's all you are, my baby! [To BIFF] And you! What happened to the love you had for him? You were such pals! How you used to talk to him on the phone every night! How lonely he was till he could come home to you!

.

Act II

BIFF: And I never got anywhere because you blew me so full of hot air I could never stand taking orders from anybody! That's whose fault it is!

WILLY: I hear that!

LINDA: Don't Biff!

BIFF: It's goddam time you heard that! I had to be boss big shot in two weeks, and I'm through with it!

WILLY: Then hang yourself! For spite, hang yourself!

BIFF: No! Nobody's hanging himself, Willy! I ran down eleven flights with a pen in my hand today. And suddenly I stopped, you hear me? And in the middle of that office building, do you hear this? I stopped in the middle of that building and I saw--the sky. I saw the things that I love i nthis world. The work and the food and time to sit and smoke. And I looked at the pen and said to myself, what the hell am I grabbign this for? Why am I trying to become what I don't want to be? What am I doing in an office, making a contemptuous, begging fool of myself, when all I want is out there, waiting for me the minute I say I know who I am! Why can't I say that, Willy?

WILLY: The door of your life is wide open!

BIFF: Pop! I'm a dime a dozen, and so are you!

WILLY: I am not a dime a dozen! I am Willy Loman, and you are Biff Loman!

BIFF: I am not a leader of men, Willy, and neither are you. You were never anything but a hard-working drummer who landed in the ash can like all the rest of them! I'm one dollar an hour, Willy! I tried seven states and couldn't raise it. A buck an hour! Do you gather my meaning? I'm not bringing home any prizes any more, and you're going to stop waiting for me to bring them home! ... Will you let me go, for Christ's sake? Will you take that phony dream and burn it before something happens?

.

King Lear

Act I, scene 2

EDMUND: Thou, nature, art my goddess; to thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom, and permit

The curiosity of nations to deprive me,

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moon-shines

Lag of a brother? Why bastard? wherefore base?

When my dimensions are as well compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape as true,

As honest madam's issue? Why brand they us

With base? with baseness? bastardy? base, base?

Who, in the lusty stealth of nature, take

More composition and fierce quality

Than doth, within a dull, stale, tired bed,

Go to the creating a whole tribe of fops,

Got 'tween asleep and wake? Well, then,

Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land:

Our father's love is to the bastard Edmund

As to the legitimate: fine word, -- legitimate!

Well, my legitimate, if this letter speed,

And my invention thrive, Edmund the base

Shall top the legitimate. I grow; I prosper:

Now, gods, stand up for bastards!

Hamlet

HAMLET: Seems, madam! nay it is; I know not 'seems.'

'Tis not alone my inky cloak, good mother,

Nor customary suits of solemn black,

Nor windy suspiration of forced breath,

No, nor the fruitful river in the eye,

Nor the dejected 'havior of the visage,

Together with all forms, moods, shapes of grief,

That can denote me truly: these indeed seem,

For they are actions that a man might play:

But I have that within which passeth show;

These but the trappings and the suits of woe

(But note Hamlet is making a point about King Claudius' lack of true feeling.)

Act 2 scene 2

HAMLET: I will tell you why; so shall my anticipation

prevent your discovery, and your secrecy to the king

and queen moult no feather. I have of late -- but

wherefore I know not -- lost all my mirth, forgone all

custom of exercises; and indeed it goes so heavily

with my disposition that this goodly frame, the

earth, seems to me a sterile promontory, this most

excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave

o'erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted

with golden fire, why, it appears no other thing to

me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours.

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason!

how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how

express and admirable! in action how like an angel!

in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the

world! the paragon of animals! And yet, to me,

what is this quintessence of dust? man delights not

me: no, nor woman neither, though by your smiling

you seem to say so.

What not to write, and breaking rules

If you’ve read some of my stories, think back on them and guess how many words were in each one (mouse over to reveal):

Story Words

Behind the Scenes 1392

Burning Man Brony 9567

The Corpse Bride 2765

Dark Demon King etc. 4317

The Detective and the Magician 14179

Mortality Report 4296

Pony Tales (all 11 stories) 8526

Sisters (my 2 stories only) 6521

Trust, not including alternate ending 1435

Twenty Minutes 3361

Twilight Sparkle and the Quest etc. 1754

Did you guess high or low? Probably high. I write succinctly. When I try rewriting someone else’s story, it usually comes out about one-third as long. I guess that’s my “style”. It’s deliberate, mostly. It’s my strength and my weakness.

One way I make things short is by summarizing things that don't need to be said explicitly. One comment the first EqD pre-reader made on “Moving On” was, “You have a habit of narrating over what could have been interesting interactions.” I defended summarizing parts of the story that don't move you towards the goal:

Being interesting isn't enough reason to put something in a story. Every paragraph must do something to achieve at least one of the story goals, and preferably two or more.

Then I quoted one of the summaries in question:

Stepping forward, she floated out the card and introduced herself as the head librarian. The only proof she had of her story was the card and the brightly-colored "Ask a Librarian!" button attached to her cardigan, but the ranking guard brightened immediately at Starflower's name.

This short paragraph does several things.

The guards are the first obstacle to seeing Luna.We see Twilight has low self-esteem.We see that Twilight thinks her main qualification to see Luna is her job.We will later recall that Twilight did not tell them her name.We see that Starflower's name carries some weight here, which increases Twilight's jealousy and lowers her self-esteem even more.

Expanding the conversation would require repeating information we already know about Starflower and the library card, and wouldn't accomplish anything more. Neither Twilight's attitude toward the guards, nor their personalities, nor anything else I could show in their dialogue would contribute to the story. It would be boring dialogue because the guards don't want anything and so aren't really story characters. Summarizing was the right decision here.

Then I looked at the other summary Pre-Reader 63.546 singled out, in scene 5:

Eventually he went back to talking about Derpy, and that seemed natural, just as every long conversation in Ponyville eventually mentioned Pinkie Pie. He leaned over and touched her foreleg lightly. "Did I ever tell you about when she invented the 'banana split muffin'? One banana muffin, one cherry muffin, one chocolate-chip—all at the same time! Just stuffs them all in and starts chewing." Twilight giggled—it was all too easy to imagine exactly how Derpy would have grinned while eating it. "So just then this cello player from the orchestra comes in, mane all tidy, spotless grey coat. Derpy sees her and runs over to tell her how good it is! Only, her mouth's still full of muffin, see?"

Joe went on to describe the inevitable scene of muffin-induced shock and outrage, and Twilight laughed as he did, less at the story than at hearing Pony Joe switch between his thick Fillydelphia accent and an eerily accurate imitation of the Canterlot mare. She re-envisioned the scene in her mind. It was so easy to imagine Pinkie and Rarity doing the same thing.

That section is supposed to:

Bring up three parallels between Twilight's friends in Ponyville and ponies now in Canterlot, suggesting that Twilight could make new friends in Canterlot if she tried.Show that Twilight can find Joe's unscholarly talk entertaining and interesting.Show that Joe and Twilight are physically closer and more comfortable with each other than in the previous scene.

And it does that. Expanding the summary into a blow-by-blow account wouldn't accomplish anything beyond that.

Yet, expanding the summary seems to be better.

"So just then this cello player from the orchestra comes in, mane all tidy, spotless grey coat. Derpy sees her and runs over to tell her how good it is! Only, her mouth's still full of muffin, see? So she leap-flies over there and gets right in the dame's face, who I don't think even knows her 'coz she says "Oh, I say" and backs away right up against that wall there." Twilight snorted and barely suppressed a whinny at Joe's eerily accurate imitation of a Canterlot mare. "And Derpy's grinning and flapping her wings and going 'Mrph mrmble mrf MRFFN!'"

Twilight re-envisioned the scene in her mind, but instead of Derpy and this Canterlot mare, it was Pinkie and Rarity. She could see exactly how Rarity would arch her eyebrows and look not quite directly back at Pinkie.

"The poor mare is frozen, she's got banana-chocolate-cherry muffin crumbs bouncing off her face like she's a statue. And then—" He tapped her foreleg again. "—and then all of a sudden she shuts her eyes and shouts, 'LENTO! LENTO'"

Twilight leaned back and took a deep breath. If only they hadn't ....

He struck the table with one hoof and laughed. "Lento!'"

Hadn't not followed her to Canterlot?

Is it better? Why? I like contrasting (my) Joe's boisterous nature with Twilight's reflective one. I like that there are some exclamation points there, in a story that doesn't have many. I wish I had a better explanation for why I should break my "Every word that doesn't work towards a story goal should be eliminated" rule here.

But I should have remembered that was a rule. And all rules are bad. Even this one.

On Moving On

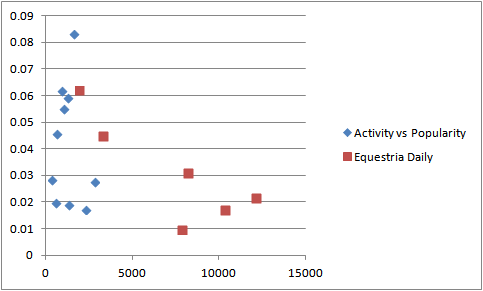

I measure how much readers enjoy stories by counting what fraction of readers who read the first chapter go on to the second chapter. I call this the Reader Retention Ratio (RRR). Things are tricky when the first & second chapters aren't released at the same time, but with a big enough sample size, you get a good idea how stories are ranked. I had a big sample—counts for the first 40,000 stories published on fimfiction. The average RRR was 0.71.